Lessons learned at Hill School

News | Published on August 2, 2022 at 2:26pm GMT+0000 | Author: Chad Koenen

0Rural school provided life lessons for young students

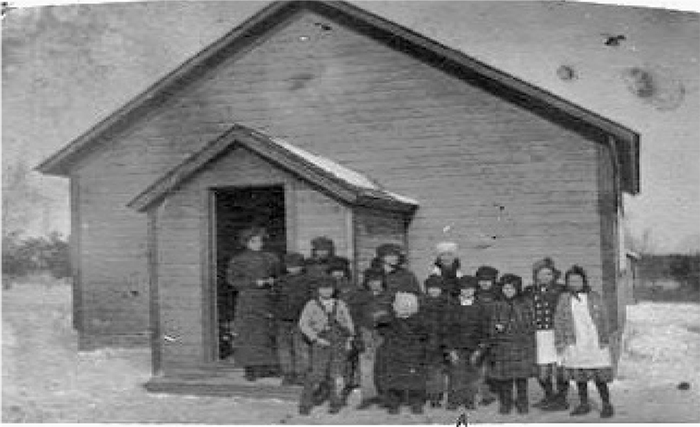

A group of students stand outside Hill School when students attended the rural school.

Editor’s Note: The following is the third article in a three part series about Bernice Johnson’s experience at Hill School.

Bernice Johnson

Special to the Dispatch

At school, the big event of the year was putting on a Christmas play. It was exciting to watch the stage appear, as we folded sheets over a rope strung catty-cornered across the front of the room. When our parents arrived and everyone took a seat, we recited poetry and sang songs. “Up on the Housetop,” “Jolly old St. Nicholas,” “Away in the Manger.”

I also have a vivid memory of performing at the school of my twin cousins, Leo and LeRoy. I had not yet started school then and had to stand on a desk so the audience could see me. Standing measuring-stick tall, I recited “’Twas the Night Before Christmas” in its entirety, while the audience beamed at me.

Leo and LeRoy’s stern German mother, Aunt Anna, came to me after the poem. She was a solemn, serious woman who seldom smiled, but she smiled at me that night, and stroked my legs, which were thick with long underwear and cotton stockings.

She said I had done a good job and excited in me a seldom indulged and never admitted desire to be the center of attention.

Leo and LeRoy were twins, six months older than I, and we liked to play in the woods when their parents came to visit. I have a photo of the three of us sitting cross-legged next to a fallen tree, our fort.

When they were ten years old, their school closed, and they came to Hill School with us.

Because I had skipped fourth grade, Leo and LeRoy were a grade behind me; I saw little of them during the day, but Norman and I walked home with them in the evenings. One day Norman said the twins and I should have a wrestling match to see which of us was strongest. I obliged by taking on my cousins one at a time, pinning their arms to the ground while I sat on their stomachs. I realize now that they let me win, but, at the time, I felt proud.

Proud is not what I felt after Norman convinced me I should kiss Lawrence Kertscher.

Lawrence was a cute little guy, younger than I. In a photo of Hill School students, a shyly smiling Lawrence stands next to me. He would walk part way home with us, then cut catty-cornered across the fields to his home. “Give Lawrence a kiss before he leaves,” Norman said. It took little coaxing. I liked Lawrence.

I leaned down and kissed him on the lips. Guffaws. Norman and Leo and LeRoy laughed and laughed at me. I was humiliating. So embarrassed I did not want to go home and hear Norman tell our parents what I had done.

While he walked home, I loitered behind and wandered through the woods, delaying the moment of return as long as I could. That was not a good idea. I cannot remember exactly what my mother said, when I finally got home but I remember her tone of voice. It was not kind. Never again did I get home late; never again did I kiss Lawrence Kertscher.

And so I learned, or should have learned, one more thing on my treks to and from Hill School. Two miles in the morning; two miles at night. Do not let anyone goad you into doing something you do not want to do.

In 1943, when he was thirteen years old, Norman left school and became a full-fledged farmer. He worked side-by-side with our father, tilling the fields and tending the horses, cattle, and pigs on our farm.

He remained a diligent and successful farmer, even after he married and had children. In 2014, he died of a pancreatic infection and complications of rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes. Yet he remains vital and alive in the landscape of my mind, where our adventures at Hill School live.

He was with the group of students who one day stood at the bottom of the path from Hill School, across from the Holstein brothers’ electric fence.

The big boys lined up next to it, and we all linked hands. I was in the middle of the chain. The leader touched the fence wire and electricity zipped from hand to hand, giving each of us a jolt that spread from our hands to our innards to our toes.

It was just like life: better and worse than I expected.

Afterword: Brother Buzzer made the trek to Hill School in 1945 and 1946. Two miles in the morning; two miles at night. Alone. When rural Otter Tail County schools merged with town schools, Hill School closed. Buzzer joined me at New York Mills Public School, where I was in tenth grade and he was in third grade.

Fifty-three years later, in 1999, Buzzer and his wife, Ruth, built a house on the Crooked Road next to what used to be Bob and Babe’s farm. Five more new houses line the road. One homeowner has vicious-sounding guard dogs that ruin my Crooked Road walks. If I can get past the dogs, walking the road is almost like returning to the past, except that light now filters between the trees where a logging crew has thinned them. The wolves that farmers got rid of in my childhood have returned to the woods, but they are few and do not worry me.

Sometimes I climb the Hill School hill. Rosie and the first Rudolph’s graves have become part of what is now known as Pine Lake Cemetery. According to a cross on one of the graves, there is one more Kohler buried there: Gust.

A plaque on a nearby Norway pine tree shows Gust was born in 1899, the same year as my father, Rudy. But my parents had never mentioned a Gust; the Otter Tail County Courthouse has no record of his birth or death. It is interesting to contemplate whether my father may have had a twin.

I stand beside the Kohler graves a while, then continue up the hill, walk around the crumbled brick foundation, and resurrect the schoolhouse in my mind. I walk to the pine trees, which are scraggly and tall now with branches only at the very top. There, I recall my days with Renzee, with Carlene, with Gordy Dertinger, and with Mildred Martin.

Mildred married a local farmer, and I have seen her only twice since our days at Hill School. Renzee and I see each other at high school reunions, where we walk and talk and reminisce. Between reunions, we exchange letters or e-mail messages. Carlene (and my book) disappeared from my life after Hill School, but there is good news about Gordy. He moved to the East Coast and married a woman who taught him how to read.