Peltoniemi finds local ties in Finland to Finnish-American triangle

News | Published on June 17, 2025 at 4:04pm GMT+0000 | Author: Tucker Henderson

0NYM musician approved for a fellowship in Finland

By Tucker Henderson

Reporter

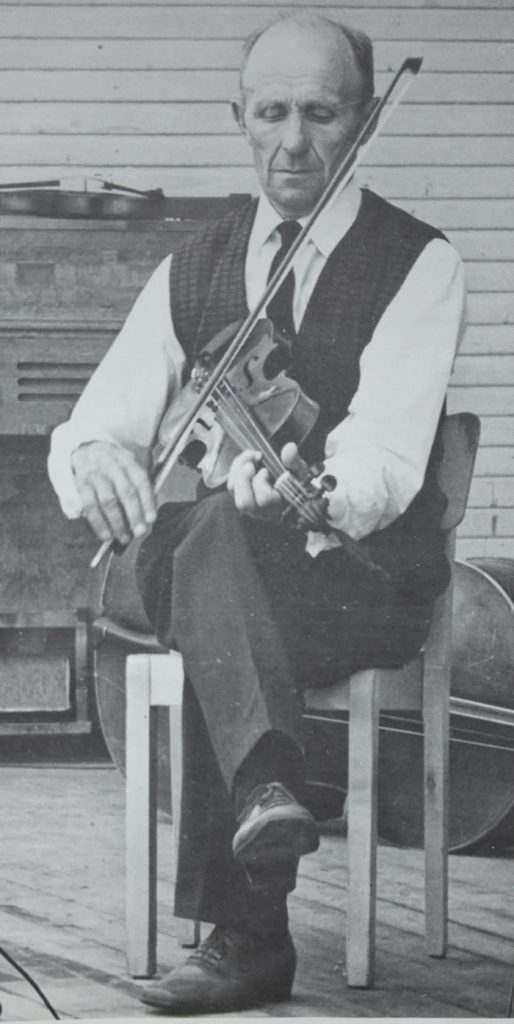

Local musician and ethnomusicologist, Karl “Kip” Peltoniemi, New York Mills, recently returned from a nearly month long trip to his forefather’s homeland of Finland to study the connection of old-time Finnish fiddle music and the people who immigrated to the area of the Finnish-American triangle.

“I applied for a fellowship from the American Scandinavian Foundation out of New York City and the application process was actually quite rigorous,” said Peltoniemi. “But eventually I got it filled out in time and low and behold, I got the fellowship. The fellowship was to go to Finland and a bit of Sweden, I wondered what type of music the original people from this area would have known.”

Having ancestry from Finland and growing up in the area, Peltoniemi has had a long lasting interest in folk music, and especially the music that his ancestors and their contemporaries would have listened to in the old country. He explained that once different musical influences from the United States and elsewhere hit Finnish-American communities, the music changed with that influence. His research focused mostly on pre-American influences from 1870 to 1910.

“There’s also the fact that people came from different areas,” explained Peltoniemi. “I’ve actually been working on developing an inventory of where they came from. Reading all those individual biographies is fascinating, even if they’re only two or three lines. The overwhelming trend in Finnish immigration was from Northern Finland first, but more than I thought, was then West Central Finland.”

As Peltoniemi explained, the beginning of the modern-day immigration of Finnish people began around the late 1860s when Finland was experiencing a terrible famine. Many Finns, looking for a better way of life, journeyed northward to Finnmark, a county of Norway which stretched eastward over the northern borders of Sweden and Norway. There, a hungry Finn and their families could catch not only fish, but some of the bolder immigrants even caught a ship to America.

“You find, even in looking at the NY Mills 75th and 100th anniversary books, some of those biographies say they’re from Norway,” said Peltoniemi. “Well, they’re not Norwegians, lots of them were from the Tornio River Valley, which divides Finland and Sweden. Then about 100 miles north, the Muonio River comes down. They are both massive rivers, they’re about as big as the Mississippi south of St. Cloud.”

South along the Tornio River and across the Bay of Bothnia lies the village of Kaustinen, where much of Peltoniemi’s research was centered. The village of about 4,300 people has a long and storied history of fiddle players, the first of which was recorded in 1707.

“The earliest known Kaustinen fiddler’s name was Wirkkala,” said Peltoniemi. “That’s also a village outside of Kaustinen that’s rich with fiddlers. We know about this fiddler because he was either fined or chastised by the church for playing fiddle on a Sunday,” he laughed. “That family line still runs thick with fiddlers.

“Kaustinen is the fiddling capital of Finland,” he continued. “There were people, especially later, who came out of Central Finland and some of them came from Kaustinen and a town nearby called Halsua. Currently at Kaustinen, they’ve got the Folk Music Institute Archives of Finland, so I was able to work in those and I was able to interview about seven fiddlers in Kaustinen.”

Peltoniemi had been to Finland four times prior to his trip in May, so he had been acquainted with several musicians in the past which made his research go a lot smoother. His friend, Arto Järvelä, is one of Finland’s top fiddle players and fiddle scholars and was his primary contact. Järvelä has been called the “busiest man in Finnish folk music” and has a very successful career in his area of expertise.

“This fiddle music in Kaustinen is really ornate and complicated and hard,” said Peltoniemi. “They have a different music and they play in keys that other people don’t play in because after 1809, the Russians took over Finland and there would be these Russian bands that played in keys like B-flat, D-flat, A-flat, so the fiddlers started playing in these keys as well.”

The fiddling tradition is a combination of some things and prior to the Russians coming, that part of Finland is fairly close to Sweden,” he continued. “There was an influence from those Swedish fiddlers and some of those tunes came across the gulf and Kaustinen players played them as well.”

As the population in Kaustinen increased, picking up a fiddle became a popular pastime at the end of the 19th century and before long, fiddling groups became a large part of the area’s culture. These groups developed their own repertoires of songs, which they played for dances and other events, including weddings.

“It was going very strong,” said Peltoniemi. “It became a very popular thing in small towns to have youth clubs, so people could have healthy fun, and so they had lessons and people would listen to old fiddlers and so there got to be lots and lots of them. That continued to build with more and more fiddlers well into the 1950s, and finally in the 1960s, it started petering out a little bit, so a Finnish music researcher came and thought that they should set up a folk music institute.

“Now there’s thousands from all over that play,” he continued. “So they were able to save it.”

Peltoniemi found a local connection to Kaustinen’s fiddle history during his first trip to Finland in 1993, when he heard about Otto Hotakainen, one of Finland’s famous master fiddlers who was born in Halsua, near Kaustinen.

“I heard that name and said, ‘I know a lot of Hotakainens,’” he explained. “After a while we found out that they’re all related. Otto died in 1990, but he was an original, incredible fiddler. He wrote so many great tunes, he was unique, and his tunes are still being played today. They will be forever.

“Otto’s father, Aleksi Hotakainen, came to Sebeka and didn’t stay very long, he decided to go back to Halsua, Finland,” he continued. “His brother, Aato and his wife, Geela, stayed and had eighteen children. So there’s a lot of Hotakainens still in this area, but had Otto’s father, Aleksi, not returned to Finland, there would be no Otto Hotakainen.”

That very realization led to Peltoniemi’s interest in the connection between Kaustinen’s fiddle tradition and the Finnish-American immigration to this area, especially centered around Sebeka and Menahga, where many immigrants who hailed from Kaustinen eventually settled.

“That made me think, how many people came out of that area that might have played fiddle and there was nobody to keep track of them and they just went off into the woods to live, those in the Sebeka and Menahga area. We know here, there were more people that came to New York Mills from more than just the Tornio River Valley.”

Along with the beginning of the Great Migration of Finns to the United States in the 1860s, the Laestadian movement within the Lutheran Church of Finland was gaining a foothold at that same time. This awakening movement would lead to many Laestadian church bodies across the world, including locally, the Apostolic Lutheran, Old Apostolic Lutheran and Laestadian Lutheran Churches.

“The Laestadian church was starting to get going really strong and they did not believe in dancing,” explained Peltoniemi. “They generally have instruments like the organ and piano, those used in a religious service and lots of singing. But when the Swedes were wanting to make sure the Finns didn’t take over, they started to make them learn Swedish in schools. Well, it’s hard to kill a language, so in everyday life, there got to be a mixture of Swedish and Finnish and has since become an official dialect called ‘Meankieli.’

“So, the Laestadians were extremely important in keeping the Finnish language going,” he continued. “Just like here, the people who kept the Finnish language going were the Laestadian church and that’s why it stayed here for so long.”

Now that Peltoniemi has been able to settle back into life in the States, he returned with a treasure trove of books, music, and digital archives that he said will keep him busy for years. Along with that knowledge, he hopes to be able to work within the local schools and pass along a taste of the tradition of the music that came before.

“I want to work in the schools a little bit. I don’t expect everyone to be interested in ethnic music, but it’s good music,” he laughed. “That would be one thing I could do, but I’ll be doing as much teaching as I can hopefully and going out wherever anyone wants me to teach.

“I’m kind of from the same environment,” said Peltoniemi about the Kaustinen area. “I’m not an academically trained folklorist, I’m a folk-folklorist,” he laughed. “I had to learn on my own.”

Working with Farmers Cooperatives and having spent his career working blue-collar jobs, Peltoniemi said that he felt at home with the people of Kaustinen and similarly, with the people of New York Mills, Sebeka, Menahga, and Wolf Lake.

“What I see in the people around here, it’s the same people you see in Finland in terms of temperament and skills,” he explained. “People have a lot of abilities to do a number of things, hard workers. I feel I was really lucky to get this fellowship and I feel I’m really lucky in the sense that I’ve got 30 years of relationships, so that gave me some ability to talk to people that maybe some others wouldn’t have.”